NOW AVAILABLE ON AUDIO BOOK!

Amazon, iTunes, Audible

An excerpt from my book about the making of the Python TV series:

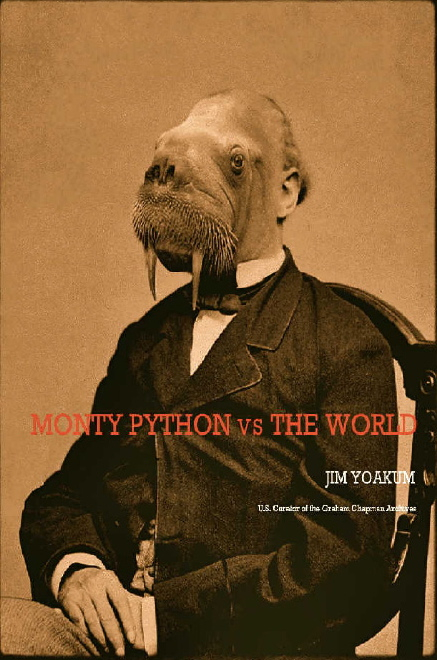

MONTY PYTHON

VS

THE WORLD

What’s So Funny About Bleedin’ Lord Hill?

This is not a fan’s book (although I am a fan), nor is this a stoic dissertation on Monty Python humor and its influence upon late 20th-century man. Those books and articles have already been written many times. This is a book about a social and cultural revolution as important in its impact as the storming of the Bastille. This is the story of “a revolution in the head” that came to us disguised as a humorous television series called Monty Python’s Flying Circus, a show that, in its way, forever changed not only television, but also the world. Accidentally.

When I first saw the series in the 1970s I, like many others, secretly congratulated myself on how hip I was to “get it all”- and then one day I came to the realization that I was missing half the jokes. Sure, I laughed along with the best of them whenever a Python Pepperpot character would talk about “bleedin’ Lord Hill” – but it was a hollow chuckle. The truth was, as an American, I had absolutely no idea who Lord Hill was or what made him so funny. That’s when I decided some serious investigation was in order, and I set out to discover more about people like Reginald Maudling, Lord Hill and Mary Whitehouse – cultural references continually ticked off in Monty Python and names that never failed to produce gales of laughter from the studio audience. The more I learned about the workings of the British Broadcasting Corporation, the prevailing British social attitudes of the times, and even the backgrounds of the group themselves, the more I realized that to truly enjoy the Monty Python television shows one needs to have more than just a well-developed sense of the absurd, one needs to understand (or at least be aware) of the times and circumstances in which the shows were written, produced and viewed. That is why this book was born. How it is that I came to write it is a different matter.

You never know where life will lead and so it was with no small surprise to find that, during the course of working on this book, I went from being a Python fan to becoming a friend of Graham Chapman’s. I got to know the man and his family personally, even working some with Graham and then, after his death, his longtime companion, David Sherlock, put me in charge of Graham’s papers and I became US Curator of the Graham Chapman Archives. It is a position I’ve held with humility, honor and pride since the 1990’s. After years of reading, collating and archiving Graham’s papers, notes, letters, scripts – even partially-written sketches on the back of an unpaid bill – I’ve been allowed a unique insight into the creative mind and methods of Graham Chapman and, to some degree, the other Python’s. I’ve also been privy to much inside information about Python, not only from the Archives, but also from my association through the decades with many key players both in and outside of the team.

Consequently, this book is not only the story of how their groundbreaking television series came to be but, in some ways “an insider’s take” on it – albeit one from an insider who was taken from planet earth in 1989. It is my sincere belief that, after you read this book, you’ll be able to laugh – and laugh much heartier – the next time you watch the Python series, secure in the knowledge that you know full well “what’s so funny about bleedin’ Lord Hill.”

Jim Yoakum

US Curator, the Graham Chapman Archives

NOTE: Except for the end section, this book deals strictly with the 5-year period (1969-1974) in which the Monty Python Flying Circus series was conceived, written and performed.

A Legal Foreword

By Graham Chapman

What can one possibly say about Monty Python that has not already been the product of a major lawsuit? Evidently quite a lot, which is why you now hold this book in your hands. And quite a nice book it is too. I dare say that there are things in here that even I did not know, and I was there at the beginning, back when Monty Python was a mere niggling legal matter, and not the full-fledged lawsuit that it would eventually become. Having said all that, I must admit that I have not, in a strict and legally binding sense, actually read this book. However I have read the brief, and I feel certain that it will make a splendid lawsuit and live on in the courts for many years to come.

Graham Chapman

July 1988

About The BBC

To try and explain the inner-workings of any large corporation is a daunting task, but to try and explain the inner-workings of a large, government controlled, corporation is perhaps an impossible one. Still, to better understand some of the motives behind the actions of people like Lord Hill, it is best to know a little something about the British Broadcasting Corporation.

At least true circa 1969-70s, the BBC (or the Beeb, or “Auntie Beeb” as it is sometimes referred) is a major public institution, and one of the country’s only means of communicating with its people. It is commercial free, and in that way it can be compared to Public Broadcasting in America, but the difference lies in that PBS is privately funded for the most part and, consequently, is not subject to the same intense pressures from “interested parties” as is the BBC. The “interested parties” with the most clout are, of course, the political ones. And while they don’t like to appear (while in office) to be manipulating the BBC, they do have one rather crude weapon that they swing over its head to ensure that Broadcasting House doesn’t go too far: the license fee.

Now we come to one of the fundamental differences between American and British television: the British viewing audience is charged an annual fee to watch TV (radio is free). This fee is set by the government and administered by the Post Office, and is the only form of revenue the BBC has apart from syndication and merchandising sales. While it is one of the cheapest services in Europe, a rise in the fee (essentially a tax) is always an unpopular political move; yet it is one that the politicians in power are willing to make – as long as the BBC behaves itself. If it doesn’t, well, you get the picture (Then again, maybe you won’t get the picture. Literally.)

During most of the 1960s the BBC was expanding. People were buying TV sets at a steady pace and, along with the introduction of color TV; this meant that it was relatively free of economic pressure. But by the late ‘60s this expansion was over. Inflation was rising, causing the BBC’s cost to rise, and they were finding it increasingly difficult to survive on their current revenue. Clearly something had to be done.

The BBC is controlled by a group of individuals known as the BBC Board of Governors. These are highly distinguished private individuals who are appointed to the post by the government. It is their job to oversee the activities of the Director-General and the Board of Management. The Chairman, who is, in turn, appointed directly by the Prime Minister, heads the BBC Board of Governors. The BBC as a whole comes under the jurisdiction of the Home Secretary, who during this time was Reginald Maudling.

Just as the BBC is under pressure from politicians, they in turn are subject to pressures from other “interested parties” – lobby groups. The most celebrated of these special interest groups was the National Viewers’ and Listeners’ Association headed by a middle-aged ex-school-teacher from Shropshire[1] named Mrs. Mary Whitehouse, the original “Hell’s Granny.”

Mary Whitehouse first became concerned about the influence of broadcasting on public morality in the early 1960s. She was a committed Christian and a former supporter of Moral Rearmament (an early, British, equivalent of the Moral Majority). Whitehouse was in an uproar about the secular attitude towards the family in schools, and their morally neutral stance towards sex education. These declining moral values she attributed to the changed moral attitudes portrayed on television.

On May 5th, 1964, Whitehouse and a like-minded woman, Mrs. Norah Buckland, held a rally at Birmingham Town Hall on the subject of declining moral values on television and, with virtually no organization, they managed to fill the hall to capacity. Their simple message was Clean Up TV. On March 16th, 1965, a more formal organization, the National Viewers’ and Listeners’ Association[2] was launched with Mary Whitehouse as Secretary. In May 1967 NVLA staged their first convention and, with the support of Malcolm Muggeridge (the host of the religious discussion program bumped to make room for Python), they formed a spin-off group called the Nationwide Festival of Light.

Mary Whitehouse presented herself as the plucky “Everywoman” who was standing up to the morally-depraved elite, however her critics claim that she was actually a theocratic bully who was driven by the Christian fundamentalist belief that women should be submissive and that homosexuality was a disease that could be cured (“Homosexuality is caused by abnormal parental sex during pregnancy, or just after,” she is quoted as saying. “Being gay was like having acne: Psychiatric literature proves that 60 percent of homosexuals who go for treatment get completely cured”). To the great swathes of people who disagreed with her (and whom she tarred as “anti-Christ’s”) she said that they should be thrown into prison.

Her critics have said that Whitehouse (who died in 2001) was a humorless woman who couldn’t distinguish between gratuitous sex and violence and sex and violence used to make a point. Whitehouse: “I never had any hang-ups about sex. As for being sexually repressed, nothing could be further from the truth. There are more hang-ups now than ever there were when I was growing up.”

Whitehouse wanted (among other things) to have the Chuck Berry song “My Ding-a-Ling” be criminalized because it “encouraged self-abuse.” She claimed that genial old Dr. Who contained some of the sickest, most horrible material (“upbraided scenes of ‘strangulation – by hand, by claw, by obscene vegetable matter’) and was nothing more than “teatime brutality for tots.”

She urged the BBC to be broadcast shows that “encourage and sustain faith in God and bring Him back to the heart of our family and national life.” She wanted Darwin to be expunged from the school curriculum; she demanded a ban on Dennis Potter, Benny Hill, Dave Allen, Till Death Us Do Part, the Beatles and, of course, Monty Python. “The way the Lord is using me,” she is quoted as saying, “is quite incredible.” Ironically, far from reigning in or taming British culture, Whitehouse instead fanned the flames and goaded writers, comedians and producers toward new levels of excessiveness, explicitly and candor.

Earning a complaint from Mary Whitehouse came to be seen the same as earning a badge of honor, while an endorsement from her was the equivalent of the kiss of death. The fact that Whitehouse – a woman who seemed to be totally devoid of humor, compassion or any personal insight – didn’t understand any of this only made it funnier – yet more dangerous.

Monty Python’s Flying Circus

On the Sunday evening of October 5th 1969, England was once again attacked from the air by the Flying Circus. Only, this time around it wasn’t Baron Von Richthofen’s, but Monty Python’s Flying Circus that was inflicting all the damage. This flying circus dropped jokes instead of munitions, and there wasn’t a single bomb in the bunch. To some viewers, being confronted by Monty Python’s Flying Circus that evening was probably a bit of a shock – they’d been expecting to see a religious discussion program. No doubt they were also confused by the fact that not one person on the program appeared to be named Monty Python.

From the first frame of the opening titles it was clear that they were (to borrow a soon to be familiar phrase) in “for something completely different.” Cartoon violence, killer jokes… this wasn’t the hip British satire of Beyond the Fringe, nor was it the comfortably corny vaudeville of Morcambe and Wise – this was… subversive. This was absurd. Silly. Something completely different. Consequently, the BBC who buried it with irregular late night transmissions and virtually no publicity relegated it to cult status.

The program’s format was a puzzler too. Gone were the conventions of normal sketch comedy with their mundane premises and punch lines, and in their place was a show that seemed not so much structured as strung-together. Ideas and in-jokes spilled one on top of another in the crazy-quilting style of a daydream. Sketches could (and did) end unexpectedly, or without a punch line altogether, and lush, pretentious build-ups could lead to nothing more than the introduction of the next sketch.

One episode contained enough ideas to sustain a hundred series, yet they were being burped out here at a rate of 20 per second. The Python’s were pushing at the boundaries of conventional comedy and were finding that they weren’t the insurmountable mountains they’d expected, but mere molehills.

Like The Beatles before them, Monty Python was a phenomenon (SNL’s Loren Michaels dubbed the {Python’s “The Beatles of comedy”) and their series was a landmark in the history of television. As Bob Hope was to comedy in the ‘40s and Lenny Bruce in the ‘60s, Monty Python was a line of demarcation of a generation. They were the harbingers of a new set of laugh lines that declared: “from now on, this is what’s funny.” The Python’s would deny this of course. They have said that they didn’t set out to shatter the conventions of comedy; that their only goal was to be funny. But the Python’s were a product of their times, and their times (the late 1960s) were calling for humor that, as John Cleese has said, did more than “make jokes about the price of fish” (Although they could, and did once did, make jokes about the price of an albatross).

Often misunderstood, and never far out of the spotlight of controversy, Python spearheaded what they called the “silly school” of humor, modeled more on the absurdities of The Goon Show rather than the satiric bite of Beyond the Fringe (their immediate predecessors), and it’s for this reason that Python humor survives today. Silly, it seems, knows no era.

Not for them the heavy-handed lampooning of That Was The Week That Was, which mocked and satirized the current atmosphere of the time, rather Python “sent-up” and mocked current modes of thought. Monty Python was funny all right, but it was funny about ideas. Perhaps it was this very style of humor which led to many of their troubles, for it goes far beyond poking fun at the price of fish and attacks the very core of why we laugh, and what we laugh at.

By avoiding the temptation to be topical (like That Was The Week That Was and, in America, The Smothers Brothers) their shows withstand repeated viewings and are as fresh today as they were when first broadcast. Monty Python’s Flying Circus set a new standard for humor, the reverberations of which can still be felt today in the style and attitudes of shows like Saturday Night Live, The Young Ones, Kids in the Hall, SCTV, Mr. Show, Flight of the Conchords, South Park, Wonder Showzen, The Mighty Boosh, Look Around You, The Daily Show, The Colbert Report, The Onion; as well as in the humor of subversive comedians like Popper and Serafinowicz, The Yes Men, Steven Wright, Emo Phillips, Clarke and Dawe, Will Ferrell (to some degree) and, of course, the late and lamented Andy Kaufman.

For better or worse (depending upon your point-of-view) it is mainly due to Monty Python (both the troupe and the series) that what was once considered shocking or insurrectionary is now regular prime time fare.

“What Python learnt most from the Absurdists (Eugène Ionesco, Arthur Adamov, the Theatre of the Absurd, etc.),” says Terry Jones, “was the importance of doing something completely different. The Absurdists were trying to do something that would shock, to stir their audience up to think in a different kind of way. In Python we were always very nervous. It was just a struggle, quite honestly, because we never knew whether it was going to make people laugh or not. I remember in the dressing room before the first sketch we did, which was Graham Chapman leaning over a fence talking about a flying sheep, John Cleese said to Mike Palin, ‘Do you realize, Mikey, that we might be doing the first comedy that nobody ever laughs at?’ It was always like that. As I recall the first showing of Holy Grail was a total disaster. Python seems funnier to people now than it did then.”

The story of Monty Python’s Flying Circus is one of accidents, calculations, inertia, bullying, apathy, enthusiasm, ignorance, intelligence, censorship and unbridled imagination. It’s the story of one television series and six men who, if not for varying degrees of all of the above, would have become doctors, lawyers, historians, advertising executives, English professors and, perhaps, politicians. (For several years Cleese was quite vocal for the Social Democratic Party, and in 2003 there were rumors he might run for mayor of Santa Barbara, California. He didn’t.)

This is the story of six extremely individual individuals whose only common bond appeared to be the desire to make people laugh (and to hopefully make a few dollars while doing it) and who came together to create the most influential and exciting comedy series of all time. It’s the story of youth versus authority, the new way versus the old, popular culture versus counter-culture, the absurd versus the accepted, the tried versus the true and of Monty Python versus the world.

Many MONTY PYTHON products can be purchased HERE

[1] Shropshire is a county in the West Midlands bordering Wales.

[2] Now known as Mediawatch-UK.